Alter Magazine

The Living Loom

Six months ago, under the glittering chandeliers amidst the joyous hum of family chatter in the AVM Rajeswari mandapam, I was married. It was the same bustling, festive hall in Chennai that had witnessed my sister’s vows a year and a half before, and thirty-two years prior, my parents'. The air, thick with the scent of jasmine, tube roses, and sandalwood incense, hummed with the celebratory melodies of the nadaswaram1

.png&w=3840&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The garment I wore was more than a spectacular costume or cherished heirloom. An exquisite sari is living, moving art; a handwoven narrative of nature and culture that captures the pulse of life itself. It holds shimmering whorls of color and history, a powerful lineage passed from mother to daughter. It is a gift so profound that even when consumed by fire, it leaves behind only silver and gold, continuing to clothe and protect its wearer to the very end.

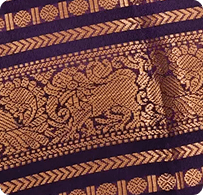

For a millennium, the Kanchipuram silk sari has been a form of wearable wealth. Upon a canvas of mulberry silk, a bestiary of mythical creatures like the lion-headed yali 2 and the divine swan, the annam3, stand guard beside towering temple gopurams4 rendered in thread.

.png&w=256&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The cornerstone of its magnificence is the zari. In its authentic form, this thread is a feat of precision: a central core of silk is tightly wound with a flattened strip of pure silver, then dipped in gold. It creates a flexible, gleaming thread that gives the fabric the weight and luster of jewelry.

This construction gave rise to a ritual that is both pragmatic and profound. In times of crisis, a grandmother could take her old saris, burn away the silk, and melt down the remaining zari. If the sari was genuine, the fire would leave behind a solid bar of silver and gold, a wearable insurance policy. It was a legacy that was liquid.

But today, the liquidity of the legacy is evaporating.

To understand the magnitude of the crisis, one must look towards metallurgy. A traditional antique sari, the kind my grandmother might have worn, contained zari that was approximately 80% pure silver and 1.5% gold, with silk making up the remaining core. It was heavy, soft, and possessed a deep, non-tarnishing luster. Today, even the "Pure Zari" sold in high-end emporiums has been diluted to roughly 45% silver and 0.5% gold to keep prices palatable in an exploding commodities market.5

Worse still is the rise of the "Imitation." If you were to burn a sari purchased from a modern emporium today, you might witness a different, darker chemistry. As the silk burns away, you would find no silver bar, but a brittle, blackened copper wire, or worse, the synthetic dust of a hollowed-out promise - a polyester filament coated in plastic film and lacquer. This fake zari is lighter, harsher to the touch, and chemically unstable; it will tarnish and fray after a dozen wears. The Kanchipuram sari risks becoming a ghost of its former self, its value degraded until all that remains is an inheritance of ash.

This material degradation is merely the physical symptom of a much deeper existential rot. To understand it, you must leave the wedding hall and travel seventy-five kilometers southwest to the town of Kanchipuram.

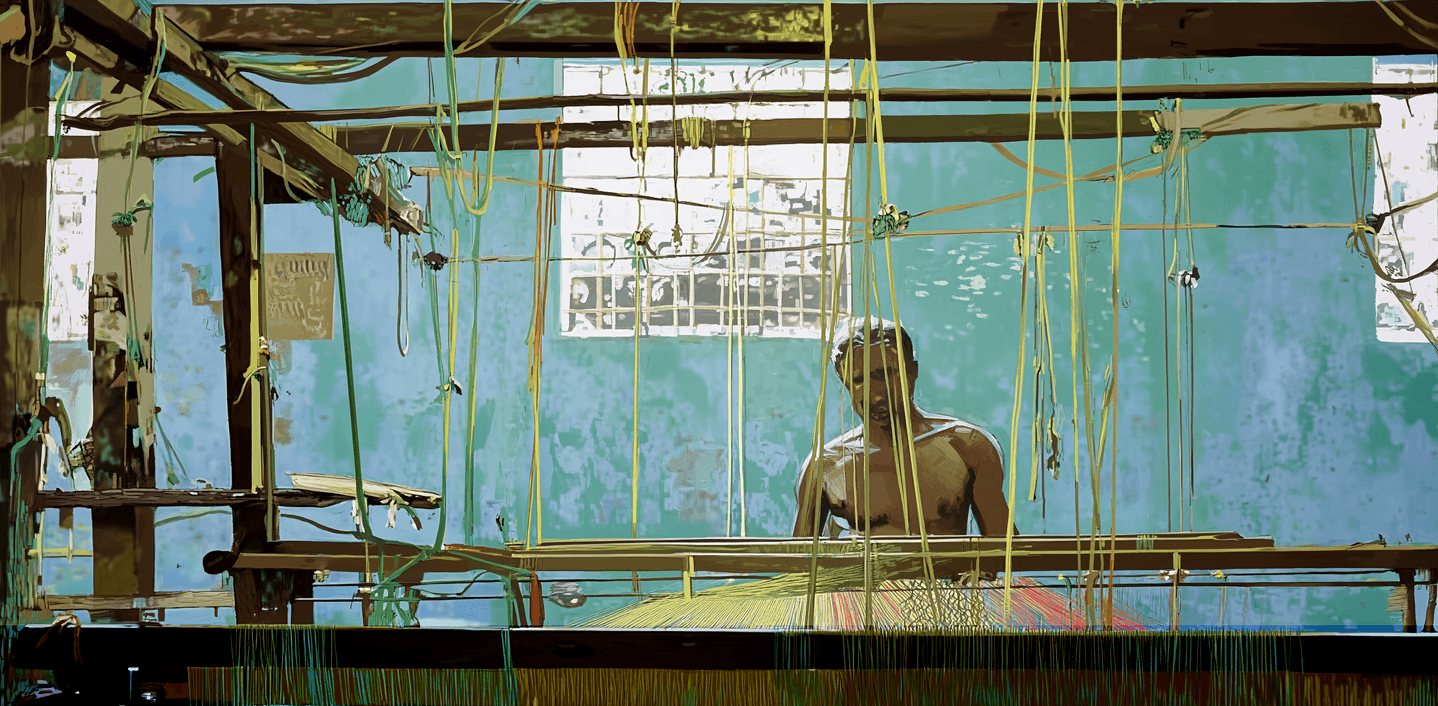

Here, in the government-run Silk Park—a sanitized, high-ceilinged attempt to provide weavers with a dedicated workspace—the air is stirred by industrial fans and the rhythmic thump-and-clatter of the Jacquard loom. It is a sound that for generations was the heartbeat of the town, emanating from the walls of every house.

-1.png&w=640&q=95&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

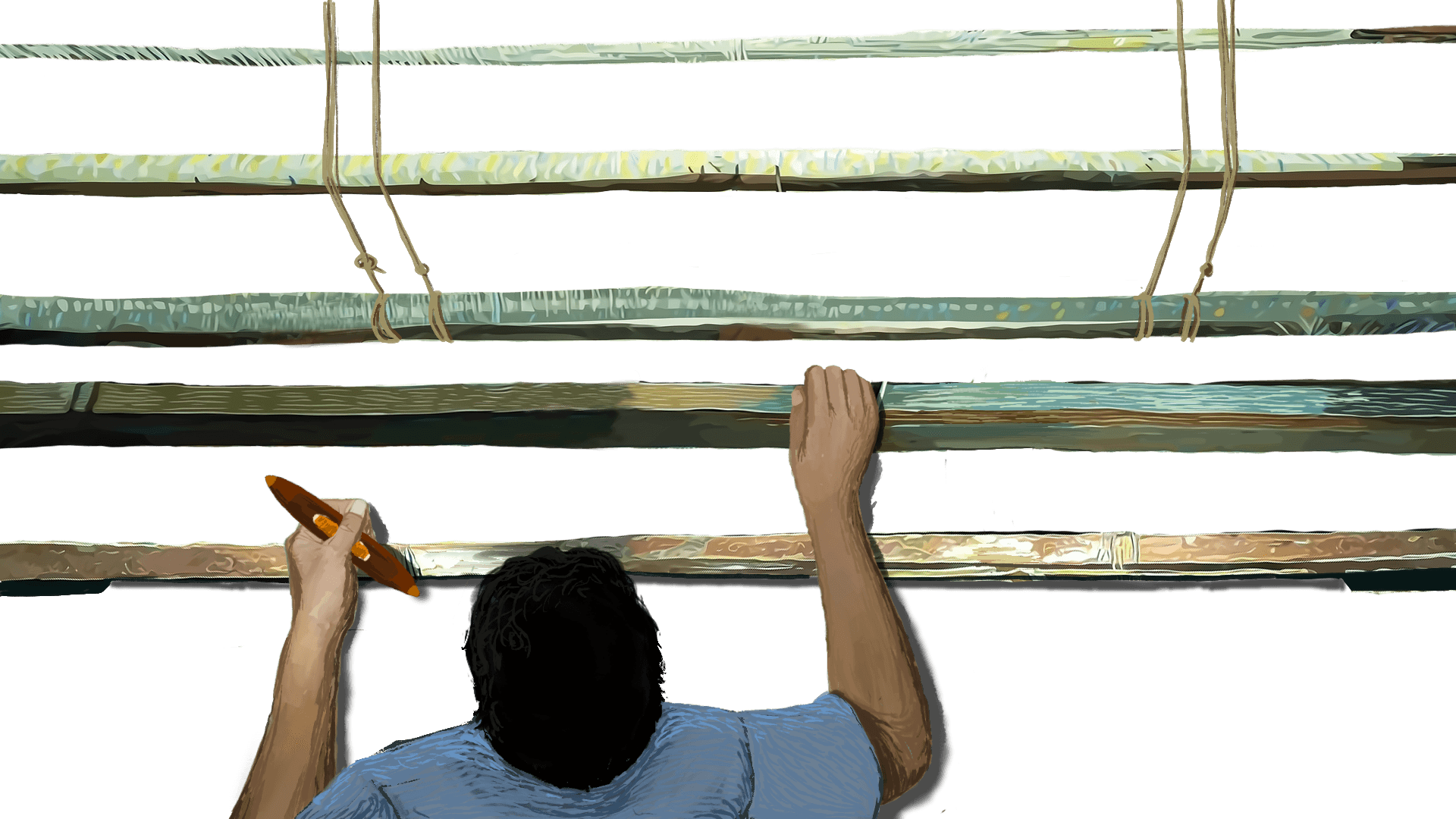

It is here that I met Hari. He has been weaving for twenty-five years, following in his father’s footsteps. His body is attuned to the loom’s complex architecture of wood and string.

The process is one of monastic patience: before a single thread is thrown, the warp—thousands of threads of raw mulberry silk—must be stretched out along the street, brushed with rice gruel to give it strength and stiffness.

.png&w=3840&q=90&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The connection between Hari's hand, foot, and eye is a feat of intuitive precision born of muscle memory.

Yet, as he wipes the sweat from his forehead, Hari speaks of an unforgiving trade. "If I take leave, there is no salary," he tells me. His profits have been gutted. As the price of gold has risen, the zari has been diluted, and his wages have stagnated.

To weave a traditional korvai 6 border—a complex, labor-intensive technique where the border is woven separately and interlocked with the body—requires the same week of meticulous labor whether the material is pure or fake. But the market punishes him for the material he is given. Where a pure-material version once fetched him ₹8,500 ($95), an impure one now earns him just ₹4,000 ($45).

The math is brutal. A "Grand Sari" might cost ₹31,500 ($350) to produce. The materials—₹18,000 ($199) for the silver-heavy zari and ₹8,500 ($95) for the silk—command the lion's share of the value. The weaver, for a week of skilled, back-breaking labor, receives a mere ₹5,000 ($55). He earns less than a plumber or a caterer in the same town.

"In the few minutes we have been speaking," Hari tells me sheepishly, "I have likely lost at least fifty rupees."

It is no wonder that the looms are falling silent. Hari’s children are raised by the village and sent to study in Chennai, seeking the air-conditioned predictability of corporate jobs—jobs with insurance, steady salaries, and weekends off. "Before, there was lots of respect assigned with this skilled job," Hari says, "now the respect is attached to how much money you earn." The youngest weaver in the Silk Park is thirty-eight years old.

No one has joined the craft in two decades.

Yet, the market for "Indian Luxury" is booming globally. We see European houses acting as colonial curators of Indian heritage: Prada rebranding the Kolhapuri chappal for ₹84,500 ($930)7; Gucci selling the common kurta as an 'exotic kaftan' for the price of a small car; and Dior releasing a ₹18,180,000 ($200,000) coat dripping in Lucknowi Mukaish work without a whisper of credit to the artisans.8 The global appetite for the aesthetic is ravenous. But in Kanchipuram, the very hands that feed this hunger are vanishing.

The crisis facing Kanchipuram is threefold and existential. The visual language of the loom is deteriorating into digital gibberish; the chemical dyes are poisoning the very water the weavers drink; and the market is flooded with fakes that have destroyed consumer trust.

In response, this story advances three audacious propositions:

- The Design: Using AI to relearn the lost grammar of the loom and restore its integrity.

- The Environment: Growing color in bioreactors to heal the land rather than poisoning it.

- The Value: Securing the unimpeachable truth of a sari’s origin with cryptographic code to rebuild trust.

Together, they ask a pivotal question: Can the tools of the digital age be reconciled with a thousand-year-old tradition, offering a path forward where heritage, regulation, and reputation have failed?

The Ghost in the Jacquard

If the first casualty of this extinction is the weaver, the second is the language itself.

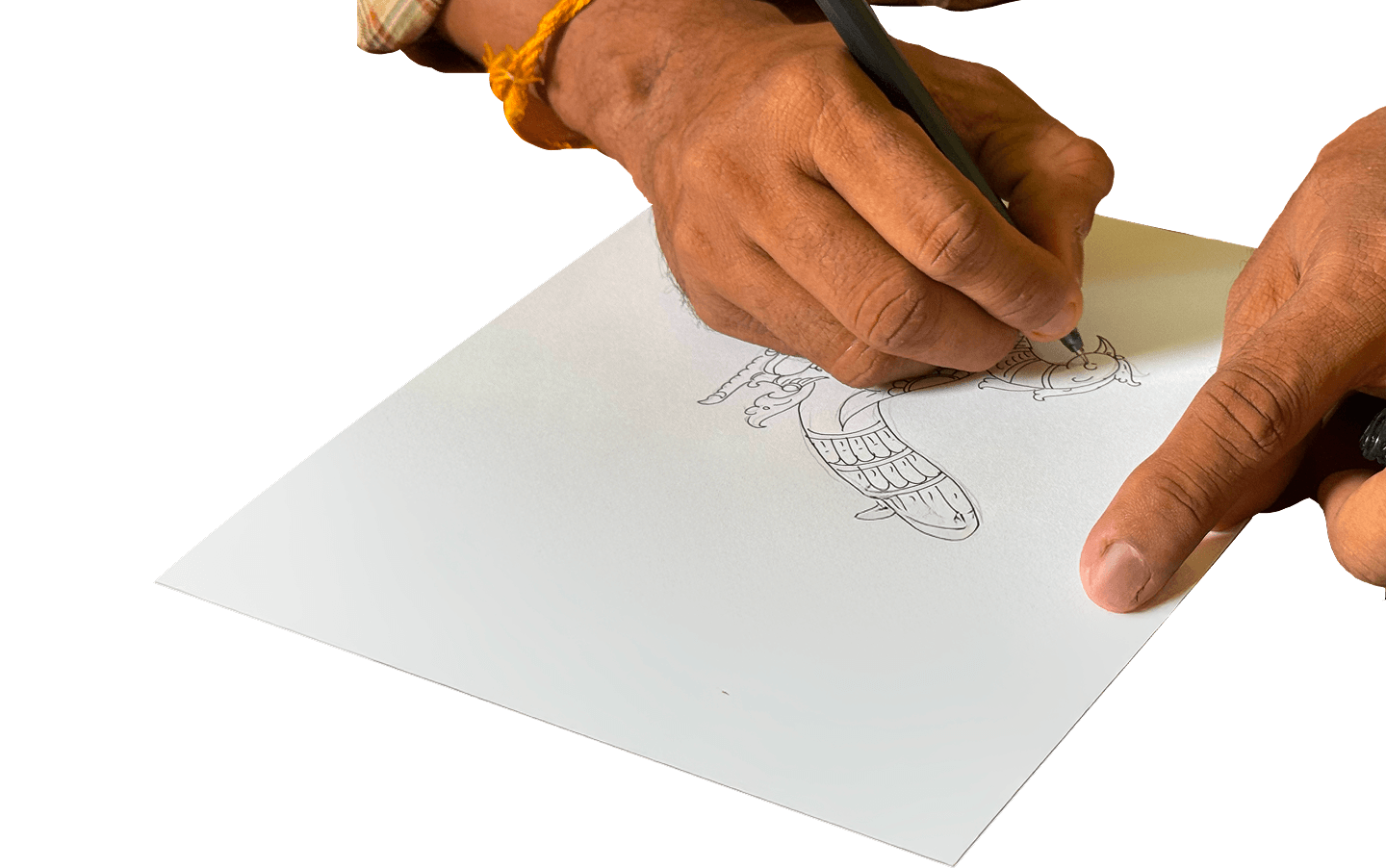

A Kanchipuram sari is not simply a patterned cloth; it is a grammatically complex text. The motifs are not decorative stamps; they are symbols in a narrative sequence. The arai madam, half-diamond, motif belongs to specific wedding rituals; the yali 9 must possess a specific aggressive posture to function as a guardian; the border must interlock with the body using the korvai technique.

%2520(1).png&w=640&q=90&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The arai madam (half-diamond) motif belongs to specific wedding rituals.

The yali must possess a specific aggressive posture to function as a guardian

.png&w=640&q=90&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The thazhamboo (screw pine) border must interlock with the body using the korvai technique.

.png&w=1920&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

"Heritage was passed down through the design itself, a story, a belief" says Harikrishnan, a freelancer and educator who lectures at the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT). He occupies the fragile bridge between the ancient jaala technique10 and the modern world of CAD (Computer-Aided Design).

In his workshop, cupboards are lined with physical archives of designs and silk samples.

.png&w=640&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

He explains that while technology has trickled down to the looms, pen drives now guide the hooks of the newest machines, something vital is being lost in the digitization. "A CAD file is just an image," he says. "It lacks soul."

.png&w=2048&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

His lament is not against the software, but the philosophy it serves. Ideally, a digital design file acts as a scaffold for the weaver’s imagination. But when used to eliminate the need for skill, it flattens a living craft into rote execution. The digital file cannot feel the tension of the yarn or the humidity in the air; it cannot adjust a motif to sit perfectly on the drape.

When a new designer uses standard software to "create" a sari, they often treat the rich lexicon of Kanchipuram motifs as a decorative buffet. They haphazardly chain together symbols, placing a kuthirai (horse) signifying a royal procession unusually next to a maanga (raw mango) which usually denotes fertility, or distorting a hamsa (swan) until it looks like a duck. The result is a "perfect" digital file that is culturally illiterate.

.webp&w=640&q=90&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

The first flicker of AI in Indian couture arrived in 2017, a collaboration between designer Gaurav Gupta and IBM’s Watson.11 It was a spectacle: an LED-lit gown that changed color based on the "personality" of the wearer. But artisans argued this was merely a "poetic search engine". It could find patterns, but it could not understand meaning.

This brings us to the fundamental flaw of modern AI when applied to heritage craft: the "Picasso Problem." Think of a Cubist portrait where an eye sits on the chin and a mouth floats on the forehead. To a human, this is abstract art; to a standard AI, it is a perfectly valid face.

Most image-generating AI today is built on architectures similar to Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). A CNN is excellent at detecting features. They scan a dataset of peacocks and learn to tick off features. But to remain efficient, they use a process called "max pooling" to reduce the spatial dimensions of the data that effectively throws away the map of where those features are located; it doesn’t know the features’ orientation, scale and relative position.

.svg?dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

Imagine an art critic looking at a painting. A CNN is a critic who says, "I see an eye, I see a nose, I see a mouth. Therefore, this is a face." It does not care if the eye is on the chin or the mouth is on the forehead. It sees the parts, but it is blind to the structural integrity of the whole.

In technical terms, the standard CNN achieves "translational invariance", it recognizes a mango motif whether it’s in the corner or the center. But it lacks "equivariance"; it fails to understand that if the sari is rotated or draped, the relationship between the yali and the border must rotate with it. It sees the texture of the craft, but not its physics.

Left: AI-generated paisley border (Gemini), where the paisley is absorbed into a continuous floral creeper, deviating from traditional Kanchipuram design grammar.

Right: Traditional Kanchipuram paisley border, where the motif remains structurally distinct from the floral creeper on the pallu.

In the context of a sari, where the geometry of the korvai join is non-negotiable and the pose of the yali is sacred, a CNN creates "gibberish", motifs that look correct at a glance but are structurally unsound and can be culturally offensive.

Even the more advanced Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)—the engines behind many deepfakes—struggle here. A GAN consists of two networks: a Generator (the forger) and a Discriminator (the detective). They play a game where the forger tries to fool the detective. While GANs are masters of mimicking texture, they often learn to create statistically plausible forgeries rather than syntactically correct designs. They might create a beautiful border that, upon closer inspection, violates the basic laws of weaving physics.

The solution to saving the grammar of the loom lies in a newer, more sophisticated architecture: Capsule Networks (CapsNets).12

Proposed by computer scientists Sara Sabour, Nicholas Frosst, and Geoffrey Hinton13, Capsule Networks were designed specifically to solve the Picasso Problem. The key innovation is the replacement of scalar neurons with "capsules": groups of neurons that output a vector.

This vector is a rich data packet. It encodes not just the probability that a feature exists (e.g., "there is a beak"), but its instantiation parameters: its precise pose, orientation, scale, and texture.

If the CNN is the sloppy art enthusiast, the Capsule Network is the trained art connoisseur. It uses a process called "dynamic routing-by-agreement". Lower-level capsules (detecting a beak) send predictions to higher-level capsules (detecting a peacock head). The higher-level capsule only activates if the predictions from all its parts are in perfect agreement. It says, "I see a beak and a crest, but their spatial relationship is incorrect. This is not a valid mayil (peacock)."

This technical distinction is the key to cultural preservation. By training a Capsule Network on a high-quality, deeply annotated archive, such as the 4,000 vintage saris collected by Santosh Parekh, founder of Tulsi Weaves, one can build an AI that understands culturally coherent grammar and the rules of the craft.

"The part of the Kanchipuram silk sari that cannot be changed is the handwoven technique. We are open to adopting anything that enables the pre-weaving process." His pragmatism is a survival tactic. "If I achieve an authentic design," he asks, "how does it matter how we get there?"

Today, his boutique designers can select, delete, and replace motifs, looping patterns and testing variations with a few clicks. They can use generative AI, not to design a whole sari but to solve sub-problems, like brainstorm trending pastel color palettes or generate eight variations of a design in five minutes, a task that would have previously taken an hour with manual use of paint. They can use it to generate reference images for designers, prompting it with queries like, "generate different species of birds with embroidery in natural colors."

In this vision, the AI acts as a Cultural Archivist. It allows a modern designer to prompt the system: "Generate a border in the style of the 1940s Rukmini Devi Arundale revival." The AI, understanding the syntax of that era, would not hallucinate a random pattern. It would retrieve the correct korvai structure and the appropriate motifs, generating a draft that is mathematically sound and culturally fluent.

But the potential for AI in textile design extends beyond grammar correction. Two other emerging technologies offer profound tools for the modern sari designer: Diffusion Models and Reinforcement Learning.

Diffusion Models represent the state-of-the-art technology behind image generators like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney. Unlike GANs, which pit two networks against each other, diffusion models are trained by a process of "denoising." The system takes a clean image and gradually adds "noise" (static) until it is unrecognizable. The neural network is then trained to reverse this process.

It learns to start with random noise and a text prompt, and then skillfully "de-noise" its way toward a coherent image that matches the prompt's description. This offers far more control and coherence than GANs. A designer could use a highly detailed prompt like, "Kanchipuram sari pallu with a central killi (parrot) motif surrounded by forest features in the style of the 1950s, using a traditional maroon and green color palette". This transforms AI from a random pattern generator into an intuitive, high-fidelity drafting tool.

Even more fascinating is the application of Reinforcement Learning (RL). This approach frames design as a "game." An AI "agent" learns by taking actions in an environment and receiving "rewards" for those that lead to a desired outcome.

Imagine a "digital loom" environment where the AI agent is rewarded for placing motifs according to traditional composition rules (e.g., correct placement of a gopuram border) and penalized for breaking them. After playing millions of these "games," the AI would learn the optimal strategies for creating a grammatically correct design, effectively teaching itself the rules of the craft through trial and error.

This leads us to a pivotal question: Does AI devalue the artisan? Many purists fear dilution—that an AI trained on a broad dataset will flatten regional variations into a sanitized "greatest hits" version of the Kanchipuram tradition. There is also the "Garbage In, Garbage Out" problem: if the digital archives used to train the AI are incomplete or biased, the AI will perpetuate that erasure.

However, a more optimistic view reframes the artisan’s role as that of a Creative Director. In this model, the designer's deep knowledge is used to write the prompts with experience, guide the AI, and curate its best outputs. The artisan becomes the guardian of the AI's aesthetic and ethical compass, using it as an apprentice rather than being replaced by it.

The industry is already seeing the first green shoots of this transition. Currently, most design boutiques rely on standard open-source CAD tools or government-backed software like DigiBunai, which digitize manual processes but offer little in the way of creative intelligence. Despite this, forward-thinking studios are beginning to look outward. Platforms like Heuritech are already using AI to analyze millions of social media images to predict color and motif trends months in advance. For a heritage boutique, this offers a data-driven way to align traditional korvai patterns with modern market appetites knowing, for instance, that a specific shade of "Cyber Lime" will be trending in Paris next season and weaving it into a classic gopuram border.

But even a design that is technically and culturally correct on the screen must eventually touch the water. And while the code is evolving, the chemistry remains fatal.

Brewing the Blue

If the design software is the brain of the sari, the dye is its blood. And right now, the blood is toxic.

To understand the price of the color that drenches the Kanchipuram silk, that distinct, vibrating "MS Blue"14 or the auspicious arakku maroon, one must look beyond the showroom lights to the banks of the Palar River. For decades, the agricultural land neighboring Kanchipuram has been a casualty of the textile industry’s liquid waste.

Left: MS Blue dyed Kanchipuram silk sari | Right: Arakku Maroon dyed kanchipuram silk sari

The crisis is even more acute in Sanganer, the famed hand-block printing hub of Jaipur. Here, the vibrant colors that adorn the town's textiles have cast an insidious shadow.15 The shift from natural to chemical dyes powered an economic boom, but it did so by contaminating the town's air and water with a cocktail of carcinogens. A recent study confirms a stark, undeniable link between this pollution and a significantly higher rate of cancer, especially among local women in breast and lung cancer. The very industry that sustains the community, employing some 25,000 artisans, has become the source of its affliction - something that we see happening in Kanchipuram right now.

"The pressure is always to finish faster," says Santosh Parekh. He recalls how the old, deliberate methods of marinating yarn overnight with natural fixatives like kadaga16 have been abandoned for the efficiency of chemical acceleration. "It's not like we want to pollute the ground," he says. "But what is the alternative?"

The alternative has historically been a binary choice: the toxic consistency of petrochemical synthetics or the erratic, scalable impossibility of natural vegetable dyes. Natural dyes are "kitchen chemistry", crushed roots and boiled insects. They are sustainable but romantic; they bleed, fade, and refuse to bind to fiber without heavy mordants (metallic salts) that can themselves be pollutants. Worse, they are notoriously inconsistent; one batch of madder root never matches the next, a nightmare for a global supply chain.

In a sterile lab in Pune, a startup called KBCols Sciences is rewriting this chemistry. They are not extracting color; they are growing it.

The process is known as precision fermentation. It functions less like a chemical plant and more like a high-tech brewery all while using 90% less fresh water and resulting in no polluting toxic waste, producing natural bio-dye powders in as little as 50 hours.

Inside steel bioreactors, specific microbes are fed a simple nutrient broth—often derived from agricultural waste or sugar. By precisely controlling the environment’s temperature, pH, and oxygen, these microbes are coaxed to secrete pure, biodegradable pigments.

These aren't random yeasts; they are often engineered from bacteria found in deep-sea vents or volcanic soil whose DNA has been mapped to isolate the specific biosynthetic pathway for a robust indigo or crimson. The environmental dividend is even higher. Because the process is self-contained in a bioreactor, it allows for near-total water circularity, using up to 90% less fresh water than the thirsty vats of the chemical industry.

It replaces the crude oil of the 20th century with a process that mimics nature’s own manufacturing code. The fermentation phase runs for just 12 to 24 hours, after which the pure color is filtered from the broth. The entire cycle, from sterile reactor to transport-friendly powder, takes as little as 50 hours.

For a delicate fiber like mulberry silk, this bio-dyeing process offers a significant technical advantage: it operates at lower temperatures, preserving the fiber’s natural luster and strength, which harsh chemical boiling often destroys. As a protein-based fiber, it possesses a natural molecular affinity for organic microbial pigments, allowing the dye to bind deeply with the silk's amino acids to create a rich, durable color without the structural damage caused by high-heat chemical fixation.

The economics are also aligning. While the raw pigment is currently about 20% more expensive than chemical dyes, the total cost of dyeing a garment is nearly identical due to massive savings in water, energy, and time. For a cotton-polyester blend t-shirt, the cost difference is negligible: ₹100 ($1.10) for chemical dyeing versus ₹102 ($1.12) for bio-dyeing.

The science of color does not stop at fermentation. To truly unlock a limitless palette, we must look to CRISPR Gene Editing.

If precision fermentation is the "factory," CRISPR is the "software" used to design the microbes. Think of it as a biological "find and replace" tool for DNA. Using the CRISPR-Cas9 system, scientists can find a specific gene in a microbe's DNA instruction manual and use molecular scissors to make a precise cut.

This allows for two powerful modifications:

- Knock-out: A specific gene is disabled or deleted, for instance, to prevent the microbe from producing an unwanted byproduct that muddies the color.

- Knock-in: A new set of genetic instructions is inserted. For example, the code for a rare flower's red pigment can be "knocked-in" to the DNA of a fast-growing yeast cell, giving it a brand new capability.

This revolutionary tool solves the main R&D bottleneck of precision fermentation. It unlocks the potential for "designer" pigments with novel properties, such as UV resistance or specific spectral qualities that natural selection never produced. While the use of GMOs faces regulatory hurdles, the potential is clear: a sustainable future where color no longer comes at the cost of the earth.17

Kanchipuram silk, in particular, has been waiting for this evolution. While conventional chemical dyeing boils the fabric, scorches the silk’s microscopic, prism-like structure and dulls its natural sheen - microbial dyeing happens at a gentle, lukewarm temperature, preserving the integrity of the protein chains, resulting in a fabric that retains its elegant drape and a color that feels deeper and more vibrant, as if it is radiating from within the fiber rather than merely painted onto it.

We are already seeing this transition towards sustainability in the West, where global luxury brands like Pangaia are deploying bacterial dyes to color their collections, and houses like Stella McCartney are pioneering biological alternatives to leather and silk. For the Indian weaver, this is a chance to leapfrog from being a polluter to a pioneer, reclaiming the word "purity" not just as a description of the gold in the zari, but as the elemental truth of the fabric itself.

Yet, the most brilliant design and the cleanest dye are rendered useless if the customer cannot distinguish them from a cheap fake.

Making of the Kanchipuram Sari

.jpg?dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

.jpg)

The Ledger: The Digital Passport

This is the "Trust Deficit." Search for a "Kanchipuram Silk Sari" on Amazon, and you will find listings for ₹3,449 ($38), or even ₹800 ($9), proudly claiming to be "Original Pure Silk Pure Zari".

These are often power-loom imitations, woven in Salem or Arani using low-quality silk and synthetic zari. They flood the market, depressing the price anchor for everyone. The consumer, unable to distinguish the masterpiece from the machine-made copy, refuses to pay the premium that the hand-weaver deserves.

For generations, the only solution to this crisis was the reputation of a few legacy family houses, like Prakash Silks or Kumaran Silks. Dr. Nalli Kuppuswami Chetti, the patriarch of the ninety-year-old Nalli Silks institution, built an empire on this "trust signal".

His life is a lesson in integrity. He started visiting the family shop at age six, incentivized by the promise of an ice cream if sales crossed ₹100 ($1.10). When he took over at fifteen, he learned a core principle from a Japanese pearl salesman in Tokyo: educate the client first. The salesman explained the nuances of pearl quality before attempting a sale, arming the young Nalli with the knowledge to spot a cheat in the very next shop.

In his shops today, saris are rigorously tested and labeled; a "Pure Zari" tag is a guarantee backed by a century of integrity. "If you never lie," Dr. Chetti says, "then you can't get caught."

But in today’s fragmented, anonymous digital marketplace, a single brand’s word is no longer enough. We need a "trustless" verification layer—a system where the guarantee is written not in a ledger that can be hidden in a back office, but in a code that cannot be erased.

Enter the Blockchain Digital Passport.18

We must look past the financial speculation of cryptocurrency and focus on the architecture of the blockchain itself: a decentralized, immutable public ledger. Imagine a Kanchipuram sari that comes not just with a paper tag, but with a digital twin—a "passport" linked to an embedded NFC chip or QR code.

A simple tap of a smartphone by someone on the Upper East Side in New York or London’s Jermyn Street or haute Paris would reveal the sari’s entire unforgeable biography. The passport contains specific data fields:

- Product Identity: Unique Product ID (UID) and Public Blockchain Transaction Hash

- Artisan & Provenance: The designer’s and weaver’s encrypted ID, names, years of experience, and the GPS coordinates of the loom where the sari was designed and woven

- Material Traceability: The specific batch of certified mulberry silk, the Silk Mark Certification, and the purity certificate of the silver zari

- Sustainability Data: The bio-dye lot number from the lab and a carbon footprint estimate

- Design Story: A narrative of the motif's meaning (e.g., the annapakshi legend) and a timestamped visual record of the weaving process

This ecosystem enables what we might call the "Distributed Hermès" model. In a recent analysis of the French luxury house Hermès, business observers noted that the brand trades at a massive premium not simply because of its logo, but because it has successfully weaponized the concept of the "Handcraft."19 A Birkin bag is valuable because it is famously difficult to make, and Hermès refuses to compromise on the manufacturing process. They verify this truth obsessively, protecting their artisans and turning them into an elite class.

India has the "Handcraft", we have millions of artisans with skills that no machine can replicate. But we lack the corporate fortress of Hermès to protect the value. Kanchipuram lost control of its truth when the market was flooded with synthetic fakes, and without verification, value collapsed. The Digital Passport acts as that fortress. It allows an independent cooperative in Tamil Nadu to prove the authenticity of their work with the same rigor as a Parisian atelier.

To understand the urgency of this, we must look at the silent crisis of the independent weaver. Unlike those in a cooperative who receive a steady wage, the freelancer exists in a state of perpetual financial lag. He often hands over his masterpiece—a garment that took 200 hours to weave—to a retailer, but payment is frequently contingent on the final sale. If that sari sits on a showroom shelf in T. Nagar for six months, the weaver waits six months for his paycheck. He is effectively an unsecured creditor to a wealthy boutique, bearing all the risk while holding none of the capital.

This is where the technology can fundamentally rewire the craft’s broken economic engine through smart contracts. A smart contract is a self-executing agreement written into code. Currently, independent artisans are trapped in this crippling liquidity crisis, waiting months for cash flow that should be immediate.

Think of a smart contract as a "Digital Hundi" for the modern age. For centuries, Indian merchants used the hundi—a bill of exchange—to conduct trade across vast distances based on trust. A smart contract replaces that social trust with cryptographic certainty. Just as the 17th-century Indian merchant used a paper bill of exchange to move value across the subcontinent without physical gold, the smart contract moves value across the supply chain without a middleman.

When the weaver hands over the finished sari to the supervisor, a scan of the NFC chip could trigger the smart contract. The code verifies the completion and automatically releases the funds from the buyer's escrow account to the weaver's digital wallet. It functions like a vending machine: if the condition is met (sari delivered), the execution is instant (payment sent). There is no middleman to delay the invoice, no ledger to be fudged.

This technology transforms the weaver from an invisible laborer into a named author, and the sari from a piece of cloth into a verified asset.

Chloé is already proving the power of authorship. Their 'Vertical' Digital ID traces the journey of their linen and silk, but crucially, it spotlights the people behind the product. It credits the specific artisan, turning transparency into a tool for funneling respect and social capital back to the maker.

LVMH, meanwhile, has solved the problem of proof. Their Aura Blockchain acts as a digital notary for their diamonds, recording the specific mine of origin and cut history. It creates a permanent, unhackable 'digital deed' that protects the stone's value forever. This is the precise intervention Kanchipuram needs: a system where the 'Pure Zari' stamp is not a trust-me promise, but a verifiable fact.

The Living Fabric

The world is ready for this. The appetite for high-fidelity, narrative-driven Indian luxury is not shrinking; it is waiting to be properly signaled.

We saw a glimpse of this future at the 2023 Met Gala. The sprawling red carpet, the literal foundation of the fashion world’s most exclusive night, was not woven in a European mill. It was hand-woven in Kerala by Neytt by Extraweave, a heritage design firm.20 Here was a counter-narrative to the usual story of cultural appropriation: a direct, credited, and celebrated collaboration. It was a powerful demonstration that Indian artistry need not be a silent source to be mined for Western mood boards, but can be a headline partner in its own right.

-1.png&w=3840&q=80&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)

Some designers are already walking this path, representing the aesthetic cousin of what Kanchipuram silk could become, a fusion of ancient technique and futuristic form. From Amit Aggarwal’s fusion of upcycled polymers with Banarasi brocade, to Rahul Mishra turning a garment into an embroidered 3D storybook that demands the world's highest stage at Paris Haute Couture Week. They are proving that the Indian loom is not a relic to be preserved in a museum, but a machine capable of engineering the avant-garde.

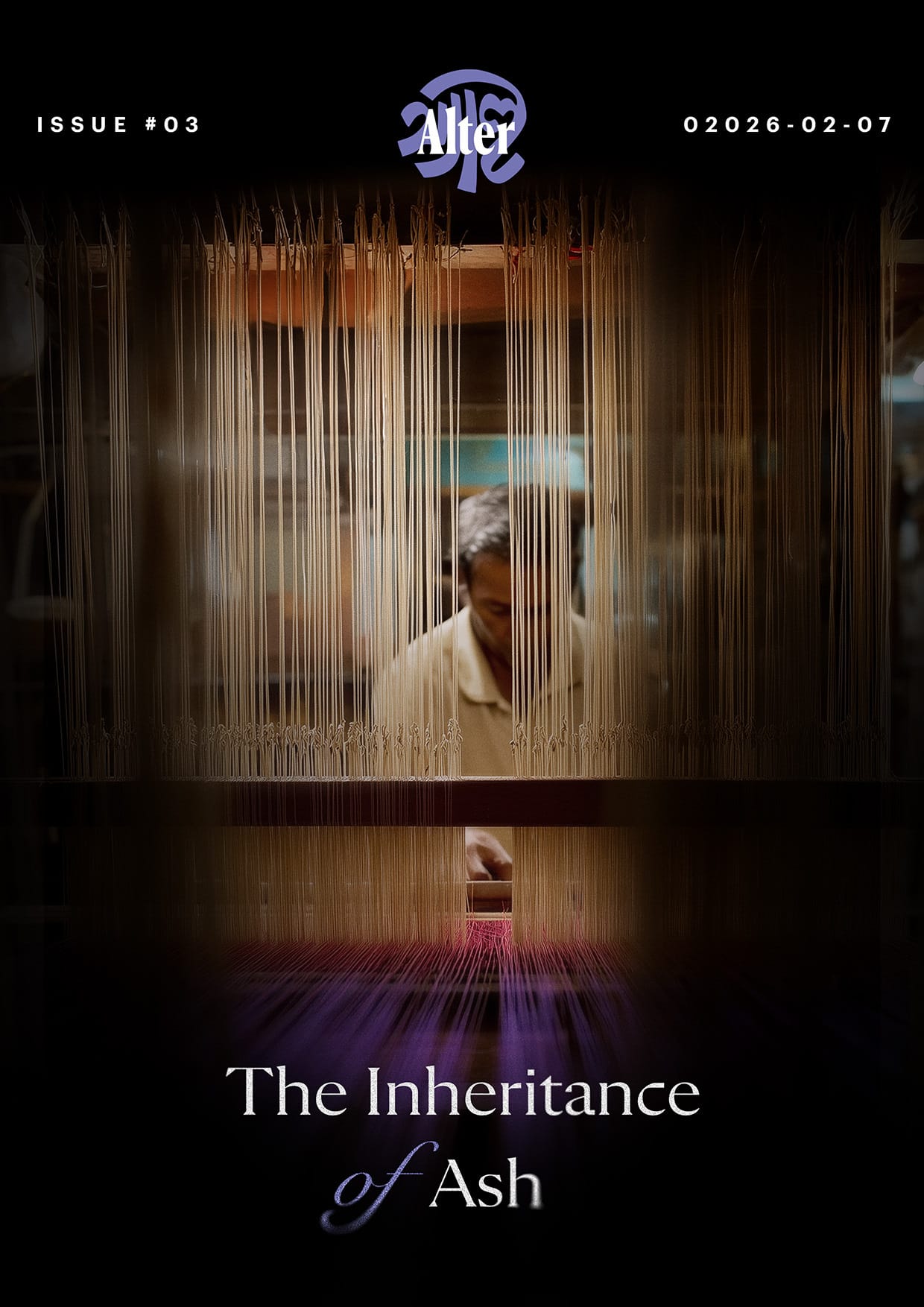

We are left, ultimately, with a choice.

We can let the loom follow the path of the "Inheritance of Ash."

In this scenario, the Kanchipuram sari becomes a zombie category; mass-produced by power looms, dyed with toxic chemicals, and sold cheaply to a market that has forgotten the difference. The weavers will vanish, their children will move on, and the museums will inherit the silence. We are currently standing in a closing window of perhaps fifteen years. Once the current generation of master weavers, now in their fifties, passes on, the "hand" that defines this luxury will be irretrievably lost.

Or, we can choose the "Living Fabric."

In this future, the weaver is not a relic of the past, but a protagonist of the future. They sit at a loom that is still hand-powered, its rhythm still the heartbeat of the town. They no longer need twenty years to master the intuitive muscle memory of every obscure motif as the AI acts as their design co-pilot, allowing them to focus on the dexterity of the weave. They use silk dyed with the clean biology of the eco-friendly future. And when they finish a sari, they tap a digital ledger that tells the world: I made this. It is real. And it is worth it.

The sari, a garment that has withstood empires, wars, and revolutions, knows how to persist. It has elegantly draped goddesses and grandmothers for a millennium. Mere survival is too small an ambition for such a legacy. It is now up to us to weave the code that ensures this ancient drape does not merely survive the digital age, but reigns over it.

Notes from Team Alter

We are a small team stretched across Alter Magazine and Alt Carbon — our bread and butter. We use AI transparently to extend visual storytelling. This article, however, refused automation. As we worked through motif grammar, loom logic, and the failure modes of generative systems, it became clear that AI could assist the telling but not stand in for the thing being told. A Kanchipuram saree is a choreography of hand, foot, and eye unfolding over weeks of labour. As we experimented with design and website development, we began to empathise with the weaver.

Even while developing this piece, the irony of using AI was not lost on us. It felt strangely full circle.

We discuss denoising in AI a lot — starting from a messy space of possibilities and slowly collapsing into a final response. That mental image of a tool took shape in our main hero section. The background is intentionally noisy: related words from the article, fragments, symbols, ASCII sketches of korvai and borders, even small hidden hex messages. It’s all there at once, before resolving into something tangible.

After weeks of experiments, we had to paint the saree in the opening visual. Every claim in the text, from motif hierarchy to AI distortion, was paired with visual proof, rendering both craft grammar and machine hallucination legible.

This position extends to the poster you see below; it centres the craftsmen, their patience, the loom, and the handiwork, foregrounding the master behind the machine.

Alter #3 was a delight to debate, design and develop. Onwards and upwards.

.png&w=3840&q=90&dpl=dpl_4ZeEJQDyNLkRgu2QtjK1ivUCM2RL)