Before Asimov, there was Rokeya.

Alter Magazine

_

One evening I was lounging in an easy chair in my bedroom and thinking lazily of the condition of Indian womanhood.

With this prosaic-sounding sentence begins a story first published in a 1905 issue of the Indian Ladies’ Magazine, printed out of Madras (now Chennai).1 On reading the opening, a contemporary reader might have thought that they were in for a genteel story of manners (whether in the comic or tragic mode), or a fictionalised memoir.

They would soon discover their mistake. Within a few sentences, the narrator – along with someone she takes for her friend, “Sister Sara” – steps out into the world of “Ladyland,” a place “free from sin and harm.” In Ladyland, men are relegated to a male version of the zenana (called the “mardana”), play no part in public life, and to be “mannish” is to be “shy and timid like men.”

Initially disoriented, the narrator soon takes to this new world with gusto – until the last sentence of the story, when “I somehow slipped down and the fall startled me out of my dream. And on opening my eyes, I found myself in my own bedroom still lounging in the easy-chair!”

The author of the story was Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. The story was titled “Sultana’s Dream,” now commonly accepted to be the one of the first significant works of Indian science fiction [“SF”] in English.2

Defamiliarisation

Crucially, from the second paragraph of the story – where the mysterious stranger who looks like “Sister Sara” appears out of thin air – “Sultana’s Dream” engages in a classic SF technique: what the contemporary Russian critic Victor Shklovsky would call “defamiliarization,”3 and what, many decades later, the science fiction scholar Darko Suvin would famously call “cognitive estrangement.”4 The technique takes a world ever so familiar, but put just so slightly out of joint by taking one of its foundational underpinnings (in this case, patriarchy), and altering that. To Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s (male) contemporaries, though, it would have been something more than that. It would have been a world made from their worst nightmares, a world alien and terrifying: another effect that SF often tries to achieve.

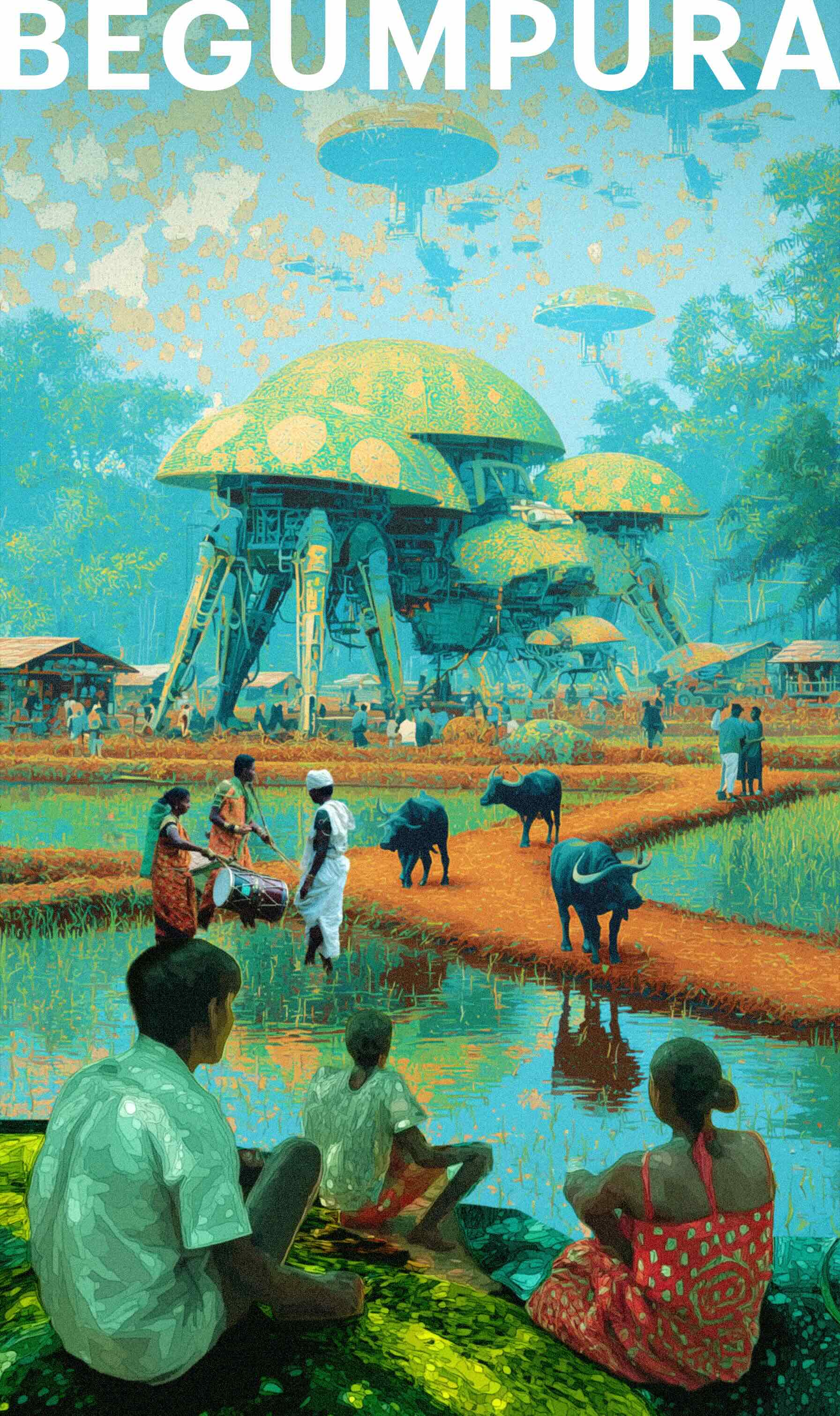

The image depicts Begum Rokeya’s imagined world, “Ladyland” — a place where men are relegated to a male version of the zenana. On hover, men appear in domestic and caregiving roles, creating a moment of cognitive estrangement.

Beyond effect, and at the level of theme and subject, “Sultana’s Dream” does two things that place it firmly within the SF tradition, albeit more as a “forerunner” – or a “foremother”5– of that tradition rather than as a participant. First, through an act of creative world-building, it interrogates and overturns existing social relations (in this case, patriarchal social relations).

A decade later, Charlotte Perkins Gilman would do something similar in her novel Herland, with its isolated society free of men altogether. In the decades to come, writers such as Ursula Le Guin, Joanna Russ, and Octavia Butler would articulate increasingly sophisticated critiques of gender and patriarchal social relations, sometimes at the intersection of race and class. This is the tradition of SF as engaged social critique, and “Sultana’s Dream” stands at the beginning of it all – not just in India, but worldwide.

Secondly, “Sultana’s Dream” envisions a utopian society where technology has solved the problems of violence, labour exploitation, and just about everything else. In Ladyland, war and crime have been eliminated, socially reproductive labour replaced by machines (which is why the men remain in the mardana and the women spend their time crocheting and cooking for pleasure), weather and climatic extremes have been regulated by advanced technology, and transport undertaken through hydrogen-powered aircrafts (this was written two years after the Wright Brothers flew for the first time). This is the tradition of techno-optimistic utopian SF, which would grip English-language SF writing a couple of decades later, and remains an integral part of the genre even today.

“Sultana’s Dream,” then, is a work of proto-SF, anticipating many of the themes that would go on to shape the genre in the 20th century. Yet the story did not spring forth from a vacuum. Speculative imaginings had long been integral to the emerging-modern literary landscape of the Indian sub-continent. Tapping into older narrative forms – the epic and the dastan – but shaped by colonial political economy, the growing influence of the sciences, and a burgeoning print culture,6 these works formed the nucleus of an early-modern sub-continental tradition of speculative fiction and its many branches, including science fiction.

From Kalpavigyan to Social Realism

The linguistic vehicles of this tradition were primarily Urdu and Bengali. Just twenty-five years after the Revolt of 1857, there was the publication of Tilism-e-Hoshruba, a hoary epic-dastan now consolidated into a single Urdu text.7 While Tilism-e-Hoshruba belongs to what we would today call the genre of fantasy or even magical realism, in Bengal there was a more direct turn to science.

Presaging a literary style that would become prominent in post-Independence India, some of the earliest works of Bengali SF were written by scientists: Jagdish Chandra Bose’s Niruddeshar Kahini (“The Story of the Missing One”), later expanded into Palatak Toofaan (“Runaway Cyclone”), written in 1896, where a cyclone is stopped by a bottle of hair oil, is an outstanding example.8

There was enough output of Bengali SF for a process of retrospective taxonomy: kalpavigyan, they called it (and still do), a word that crudely translates into “science imagination.” 9

In the early 20th century, Indian SF would expand further into other languages.10 In Baeesveen Sadi the Hindi writer Rahul Sankrityayan, much better known for his novels of social realism and for classics of historical fiction and travel literature such as From the Volga to the Ganga, imagined a utopian society set in 2124 (two centuries from the time he was writing).11

The timing of Baeesveen Sadi is interesting in its own right. Just a few years earlier, the Soviet Union had come into existence, with its avowed goal of bringing utopia on earth. It took very little time, however, for the dream to sour into the Leninist authoritarian-bureaucratic State. As early as 1919 and after, fellow-travellers of the Revolution – anarchists, avant-garde artists, poets – had begun to ask questions.12

Not for the last time in history, some of the most biting critiques took the form of science fiction: in particular, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, an early forerunner of the kind of dystopian SF whose most famous mid-20th-century articulations would come through novels such as 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451.13 Almost exactly contemporaneous with Baeesveen Sadi, We is the classic story about the dream of a perfectly-planned, perfectly-ordered Utopia which swiftly and inevitably decays into a totalitarian nightmare.

Was the well-travelled and erudite Sankrityayan aware of We when he penned his own Utopian imaginings? It is unlikely. While Sankrityayan would go on to become a communist and stay in the Soviet Union for an extended period of time, this did not come about until more than a decade later. These are, however, texts in conversation from a time when, regardless of what it was doing to its own people, the Soviet Union stood as a beacon of hope for revolutionaries and Utopian dreamers all over the world.

Feminist Utopias and the Social Imagination

Baeesveen Sadi is also, of course, in conversation with Sultana’s Dream, with the far future Utopia of the former standing in for the dream-world of the latter. Two things, however, make Sultana’s Dream a singular achievement. The first is that it is written in English. So, unlike her peers, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain did not have a literary tradition of her own to call upon, even peripherally. And secondly, it is written by a woman, with a cast of characters that are only women.

In 1905, women’s active participation in the public sphere – including through the production of literary texts – was not unknown. Women were protagonists in radical movements for equal rights, and this involved public writing, whether it was Tarabai Shinde’s arguments for gender equality in Stree-Purush Tulna,14 or Rukhmabai’s closely argued letters to The Times of India during her long court battle to avoid being forced to live with her husband.15 This participation, however, had yet to fully translate into the domain of fiction (especially genre fiction), or to find a voice in explicitly feminist themes in that fiction.

That is why Sultana’s Dream stood alone and why, perhaps, it would continue to stand alone until after Independence. Although experiments in genre fiction (as noted above) continued in a range of non-Anglophone languages, we do not see much of that writing in English. And although Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain herself published another work of SF, Padmarag,16 the further evolution of the genre in English would have to wait a few more decades.

II.

Counter Cultures in English SF

Through the course of the 20th century, English-language SF, in its heartlands of the United States and the United Kingdom, went through several phases of evolution. SF as popular literature had its beginning in the “pulp magazines” of the 1930s, often combining a techno-optimistic bent with an easy, accessible style. This was followed by the so-called “golden age” where, under the stewardship of towering editorial figures such as John W. Campbell, SF came to be characterised by sweeping, ambitious ideas around the exploration of time and space, backed up by a heavy dose of “science.”

The politics of the era were mirrored in both the writers and the audience. The mainstream of the genre – aside from a few notable dissenting voices17 – reflected “Golden Age” science fiction’s fascination with pioneering space exploration.

This fascination often echoed imperial fantasies, now reimagined on a galactic scale during an age of decolonisation. These imaginative voyages into space were accompanied, inevitably, by Cold War anxieties, especially fears of nuclear war — understandable, given that these were the 1950s.

Needless to say, this could not last. The radical and counter-cultural social and political movements of the 1960s found their way into SF. Even as names like Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein continued to dominate the field, for the first time, in the United States, women and black writers achieved a degree of fame and prominence. In their novels, Ursula Le Guin and Joanna Russ explored the boundaries of gender and alternative forms of social organisation. Samuel R. Delaney tackled the limits and the emancipatory potential of language. No longer was space, or the “hard sciences,” the defining features of SF. The genre was now asking questions about society, about the way we live, about the conceptual cages within which we exist and, occasionally, hurl ourselves against the bars.

The sudden acceleration of technological development in the decade that followed found a response in SF. William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) quickly established itself as a cult classic, coining the term “cyberspace” and inaugurating the still-relevant genre of cyberpunk. Building up to the 21st century, SF was exploring the incoming digital age through novels of ever greater finesse and sophistication, culminating in books such as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), the title borrowed from a type of software failure on the early Mac computers.18

While English-language SF has been parochial at the best of times, the mid-20th century was not without cross-linguistic and cross-cultural conversation. The primary interlocutors were from beyond the proverbial “Iron Curtain.” Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris (1961) – further immortalised by Andrei Tarkovsky’s film of the same name – with its sentient ocean that projects back into human minds their darkest fears, was critically acclaimed when it came out, and has an undisputed place in any attempt to construct a global SF “canon.” From the Soviet Union, which had given to the world Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We so many decades ago, the Strugatsky Brothers made themselves known, after a long period of censorship and repression, with their stories of human hubris and parables of environmental destruction. The most notable example of this was the eerie and defamiliarising Roadside Picnic (1972), also adapted by Tarkovsky under the name Stalker.

Tech Evolution & Sci-Fi Dystopias

This brief – and admittedly reductive – history is worth summarising if only to note the stark contrast when it comes to post-Independence Indian SF.19 If there was something of an international conversation going on with respect to genre (whose lingua franca would necessarily have to be English), India remained a silent spectator. And as far as English goes, barring the odd, Rushdie-esque foray into magical realism, it would seem that the sheer heaviness of the post-colonial English-language Indian novel, weighed down by the gravity of its themes and the seriousness of its style, suffocated any attempts at mere speculation. Of course, this is a form that in many ways still continues to dominate our imaginations.

On the other hand, while genre writing did continue in non-English languages, it remained firmly ensconced within its own set of traditions. Satyajit Ray’s series of Professor Shonku novels in Bengali (1965 onwards), and the works of Sujatha (En Iniya Iyanthira, for example, which was serialised and also the inspiration for the Tamil movie, Enthiran [Robot]) and Sorga Theeyu (Heavenly Island) in Tamil,20 are classic examples of this phenomenon: works of SF that remained siloed off both from genre writing within the country as well as from the evolution of the genre abroad.

Revisiting Rajinikanth’s blockbuster film, Enthiran and its viral “Black Sheep” moment. The video reflects on how design reframes memory, fandom, and the spectacle of technology in Indian cinema.

In an excellent piece, the Indian SF critic Gautham Shenoy writes about the late-20th century Indian SF writing dominated by scientists, who wrote in their local languages, as an era of “scientifiction,” a term originally coined by Hugo Gernsback, and what Shenoy himself refers to as “entertainment intermingled with education.”21

Shenoy focuses on the works of Bal Phondke (Maharashtra), Jayant Narlikar (Maharashtra), Rajashekhar Bhoosnurmath (Karnataka), Sujatha and Nellai Muthu (both Tamil Nadu), and Dinesh Chandra Goswami (Assam), all of whom had day jobs that involved them in some capacity with the physical sciences, as authors of scientifiction.

Form, Function, and the Patriarchal Protagonist

The lack of translation – and conversation – across languages and boundaries, however, would have its inevitable effect. For instance, a stark example of the yawning gap between the trajectory of the genre in India and abroad can be understood by a reading of Jayant Narlikar’s Virus (2003).22 Until his recent passing Narlikar, who was an astrophysicist by training, had a good claim to be regarded as India’s most respected post-Independence science fiction writer.

As the title suggests, Virus is a story about the infiltration of global computer systems by a mysterious virus, apparently by an alien intelligence – a theme (and trope) well-known to SF. But Virus has none of the thrill-a-minute aerial dogfight sequences of its close contemporary, Independence Day (although it does have scientists as protagonists). The book is absolutely choc-full of acronyms for various institutions and phenomena (bracketed expansions of the acronyms frequently break the flow of the reading).

The narrative involves lengthy, third-person, omniscient narrator-driven interjections to explain scientific theories and concepts. Sometimes, this explanation comes through “as-you-know-Bob” style expository dialogue between scientists. In Virus, form is secondary; explaining the scientific basis underlying the fiction is primary.

Virus is dedicated to Fred Hoyle, whom Narlikar describes as his guru. In many ways, this is telling. Fred Hoyle – like Narlikar, an astrophysicist by training – wrote a set of science fiction novels both by himself and with other collaborators (especially his son, Geoffrey Hoyle), from the 1950s to the 1980s. In some ways similar to Narlikar, many of these novels tended to be centred around a fairly heavy-duty (for lay readers) scientific conceit, and spent significant time explaining the science – to a point at which one can almost say that the science exposition in these books outweighs the science fiction. Indeed, given Narlikar’s own stellar career as a science educator and his firmly held convictions on the importance of scientific thinking, this should not come as a surprise.

However, while an intentional lack of attention to form might have worked in the 1950s or 1960s, by the early 2000s it comes across as dated and anachronistic, as do the novel’s gender politics (the scientist-protagonists are men, and when we see a rare woman in the narrative, she soon goes back to “polishing her nails” – somehow, we seem to have regressed from Sultana’s Dream!).

Virus, then, succeeds at multiple levels as a work of science exposition, of instruction, of acculturation. Does it, however, succeed as a novel? That question is fraught, and probably depends upon the time. Virus would not have been out of place in an era in which prose was often (though by no means always) treated as secondary to the “big idea” of a science fiction novel. But if English-language SF had grown and evolved from that over the previous five decades, it would seem that Indian SF in the second half of the 20th century had kept to a different trajectory.

III.

Hybridity, Intertextuality and Inclusivity

Perhaps one of the most uncontroversial statements about English-language Indian SF is to say that at the turn of the century, the publication of Samit Basu’s GameWorld trilogy (2004-2007) heralded a new era in the genre.

“Hybridity” has often been a term used to describe Indian genre fiction:23 the hybridity that comes with inhabiting at least two languages (one of which is English) and at least two literary traditions (one of which is English); the hybridity of growing up with Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Asimov’s Foundation on the one hand, and the Ramayana and Mahabharata on the other; the hybridity of “Hinglish.”

It is a hybridity that is most memorably articulated in a novel like Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990), where tropes of the English fantasy novel rub shoulders with highway jingles from the Himalayas – a novel that is part Alice in Wonderland and part Tilism-e-Hoshruba. And it is that hybridity that characterises Basu's The GameWorld Trilogy, which joyously plunders a range of sources and traditions to craft what would be immediately recognisable as genre to an English-language SF reader, but which is also unmistakably Indian.24

With the GameWorld Trilogy, Indian SF re-entered the global, English-language conversation – and not a moment too soon. So far, this century has been referred to as the “rainbow age of SF,” a term I am not entirely comfortable with but one that does capture something essential about the way that the genre has evolved in recent years.25

With the rise, in particular, of online zines dedicated to “SFFH” (science fiction, fantasy, and horror), there has been an efflorescence of new writers. Because of the partial lowering of entry barriers, many of these writers belong to sexual, gender, or racial minorities. This, in turn, has reflected back on the themes that contemporary SF is willing to tackle: from gender identity in Anne Leckie’s Ancillary Justice (2013) to human-octopus first contact in Ray Nayler’s The Mountain in the Sea (2023).

Plural Futures And India's Genre Fault Lines

The conversation has also become globally more diverse. The success of Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem (2008) led to an explosion of translated Chinese science fiction into the English-language market, a genre “boom” reminiscent in some ways of the Latin American “boom” in the 1960s. Meanwhile, “Afrofuturism” and “Africanfuturism” are terms that have long been familiar within the SF industry – and now, to an extent, outside the industry as well. While questions remain about how publishing power remains concentrated within the Global North, there is little doubt that English-language SF is, today, at least relatively more global than it has ever been.

What of India? In terms of volume, the last decade has seen a growth in the number of English-language SF books being published by Indian writers, to the point where perhaps for the first time in history, the question “Is there something distinctive that we can call Indian SF?” can even be posed.26 As with all such questions, there is danger in categorisation, in excluding through inclusion;27 and the creating of canons is always a political act. What follows, therefore, is not meant to be a “list” of contemporary Indian SF or of contemporary Indian SF writers,28 but rather, a broad-brush outline of some of the themes that preoccupy contemporary Indian SF, and the contexts in which they do so.

A good – albeit potentially perilous – place to start with is anthologies. The most expansive such attempt in recent years has been the two volumes of the Gollancz Anthology of South Asian Science Fiction (2019). In my review essay of Volume I of the anthology, I identified three themes that ran through the collection of otherwise distinct stories: first, a concern with the growth of technology, and its impact on the existing social and political cleavages in India; secondly, with climate change and the “unevenly distributed” future that it would bring for a country like India; and thirdly, how India’s recent history of social violence (on the lines of religion, and caste, and gender) informs its present and constrains its future(s).29

Beyond the Gollancz Anthology, I think this schema – with one addition that I will discuss below – presents a helpful approach to understanding contemporary Indian SF.30 To live in India today is to be keenly aware of each of these three fault-lines that run through our society. Perhaps the largest set of contemporary Indian SF works, therefore, is set in the near future, where these fault-lines can be probed at the point of occlusion.31

Geographies of Dystopia

Consider, for example, Aditya Sudarshan’s Idolatry (2024). Set in a near-future Bombay, the major premise of Idolatry is the invention of “Shrine Tech,” a technology that gives everyone access to their own wish-fulfilling (AI-)god in the privacy of their own homes. To no-one’s surprise, access to this technology is commercialised, and mediated by wealth and power, setting the stage for an all-too-familiar social conflict.

To understand where a novel such as Idolatry is coming from, one has to understand a large number of interconnecting strands of the nation’s past and present: from India’s national biometric identification system (Aadhaar) with its attendant concerns of mass surveillance and digital exclusion, to Bombay’s recent troubled history of riots and social violence; from the paradoxes of how private religion in India has become a public act (and vice versa), to a hollowed out State and society where even faith has become subsumed into corporatist social relations. It is that which makes it a quintessential example of contemporary Indian SF: at one level, Idolatry can be read as an SF novel that could take place anywhere, a cautionary tale about how even potentially emancipatory technologies can be distorted under capitalism to serve an oppressive purpose. This is an argument that SF has been making for decades. But then, Idolatry couldn’t take place anywhere else: the story that it tells, in all its richness and complexity, is drawn from the fabric of Indian life.

Indeed, a number of novels have explored different strands of this web. Lavanya Lakshminarayan’s Analog/Virtual (2020) (republished in the UK/US as The Ten Percent Thief) is set in a near-future Bangalore, where the digital divide has translated into a spatial and geographical divide, the city divided between the “virtuals” (who have it all) and the “analogs” (who have nothing).

Spatial segregation is also at the heart of Prayaag Akbar’s Leila (2017), where the Indian city’s long and troubled history of enforced ghettoization (along caste and communal lines), further entrenched through unequal access to basic facilities (in Leila, it is water), is projected into a frightening and cruel future. Anil Menon’s Half of What I Say (2015) presents an equally frightening future of digital dragnet and a political dystopia where any semblance of democratic power has long been ceded to a secretive and very powerful “anti-corruption bureau” (to some, Menon’s novel, written in 2015, might feel almost eerily prescient). Perhaps the lightest of works on this spectrum is Samit Basu’s Chosen Spirits (2020) (republished in the US/UK as The City Inside), set in a near-future Delhi where digital curators document every moment of their lives, and it is tedium rather than a constant fear of annihilation that is the dominant emotional register.32

“The future is already here,” William Gibson once famously wrote, “it’s just not evenly distributed.” A particularly apt choice of words for a country where the levels of inequality are now worse than they were under colonial rule. In a world in which technology is often too quickly – and too easily – presented as a solution to intractable social problems, one of the roles that Indian SF is occupying, as articulated through these novels, is that of an anti-technocratic literature.

Universalism

Two recent SF works – Varun Mathew’s The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay (2019) and Gigi Ganguly’s Biopeculiar (2024) – take opposite approaches to the issue: of urgency and of whimsy.33 Mathew’s novel is set in a near-future Bombay, now flooded and uninhabitable, with its denizens resorting to various new forms of living to survive (religion plays a significant role). In The Black Dwarves, the crisis is very real and very urgent.

Biopeculiar, on the other hand, is a mosaic novel that seeks to reconstruct our severed connections with the world around us. The stories in Biopeculiar invite us to inhabit the other, which we are destroying in the daily processes of capitalist extraction: animals, fish, even clouds. Empathy for the non-human world has long been one of the preoccupations of SF, and that is the tradition of writing to which Biopeculiar belongs. Both these perspectives, in turn, are contained within Reunion, Vandana Singh’s story in the Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction (Vol. 1), which – in the memorable words of the critic Gautham Shenoy – introduces us to the “language of Gaia.” 34

In different ways, all these works straddle the intersection of the three axes discussed above. A major part of the science fictional tradition, however, has always existed beyond the bounds of “national literatures.”35 While no writer or text can ever fully escape the limits of their own horizons, the ability to set stories in the far future, in space, or in alternate, imagined worlds means that those horizons need not fully determine such stories. For a while, the imperatives of the US/UK-based publishing industry, under which US/UK writers from Isaac Asimov to Anne Leckie were free to explore universalist themes, while writers from elsewhere were treated as “representatives” of their national cultures and therefore expected to write works closely identified with that culture, hindered the development of (say) Indian space opera, or Indian cyberpunk. That has, however, begun to change. Consider, for example, Amal Singh’s 2023 story, “Notes from a Pyre,” published in the Deadlands Magazine. Set in 2198 AD, in an indeterminate place on “Terra” (SF’s coded stand-in for Earth), “Notes from a Pyre” is an account of the funerary practices of species from different planets. The form is one that we find in the stories of Borges; in SF, it was arguably pioneered by Ursula Le Guin and, most recently, has been used by Ken Liu in The Paper Menagerie. Singh’s deft and confident use of the same form is both a laying of claim to this international tradition of SF, but in a language that is Indian-inflected: the story’s protagonist is named Parikshit Mehta, and ghevars play an important part in the story. This is, thus, a science fiction story that leans into a form that is international, but whose flesh and blood is Indian.

In the domain of the novel, Samit Basu’s The Djinn-Bot of Shantiport, Lavanya Lakshminarayan’s Interstellar Megachef, and this essayist's The Sentence are all examples of science fiction novels, published within the last two years, set either in space or in wholly imagined alternative worlds, and exploring universalist themes. At the same time, like Amal Singh’s story, these works are peppered with references and signposts that unmistakably mark them as novels written by Indians.

But the importance of taking these works seriously lies in the fact that alone among genres, it is SF that is most uniquely positioned to escape the confines of a “national literature.” It is SF whose world-building, penchant for “cognitive estrangement”, and claims to universalism allow an imaginative escape from the confines of the nation-state.

Anti-Caste Futures

While the development of literature is never linear, and regression is as likely as progress, this nonetheless heralds some tentative hope for the future of Indian science fiction that need not be constrained within the Indian nation-State as the geographical and imaginative boundary of its vision. If, therefore, we began this section by asking whether there exists something called Indian science fiction, we can end by making a seemingly paradoxical claim: yes, there exists an Indian science fiction, but it can exist beyond India.

IV.

In December 2024, after the culmination of a successful fund-raiser on Kickstarter, Blaft Publications brought out the Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF, an anthology of stories, poetry, graphic narratives, and visual art, created by Dalit-Bahujan writers and artists. In the book’s launch event at the Champaca Bookshop in Bangalore, the editors noted how English-language Indian SF, in its obliviousness to the question of caste, could be as alienating as the SF imported from beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF was an attempt to change that, in the time-honoured tradition of “writing back.”

It is obvious that to the extent that Indian genre fiction fails to critically reflect upon its own practice – and how that practice maps on to existing social hierarchies around caste, religion, gender, and sexual identity, among others – it will never be a literature of liberation. Rather, it will only replicate the insidious forms of gatekeeping, exclusion, and erasure that have historically characterised the relationship between “Global North” SF and its counterparts in the “Global South.”

The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF, thus, is both marker and manifesto.

But more than that, it is the wheel turning full circle. A hundred and twenty years ago, English-language Indian SF had its start in a utopian, anti-patriarchal short story written by a Muslim woman. One can imagine Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain looking upon the work of these, her literary descendants, and smiling.

The road is long, but we can only make it by walking.

Prem Panicker is the editor of this volume and a pioneering figure in Indian digital journalism. A founding member of Rediff.com and former Managing Editor at Yahoo! India, he helped shape the country’s early online news ecosystem. Now an independent writer and mentor, he focuses on narrative journalism and long-form storytelling, exploring how media, culture, and technology intersect in contemporary India.

Notes from Team Alter

None of these book covers actually exist. They’re our playful imagining of a world where every Sci-Fi classic would have its own collectable illustrated edition, à la Climate Studio.

This poster responds to Gautam Bhatia’s call for Indian science fiction as a ‘literature of liberation’ by framing caste as both a social and economic design problem. Drawing on Guru Ravidas’s ‘Begumpura’ and Kancha Ilaiah’s Shepherd’s critique of labour as the engine of caste exploitation, it reimagines technology as a medium of redistribution, rather than extraction.

Beetle-inspired biomimetic harvesters, floating solar cooperatives, and autonomous delivery systems propose a world in which automation dismantles the asymmetry of manual labour and the structures that sustain caste oppression through economic dependence. Guru Ravidas's imagining of Begumpura is a "city without sorrow" that is casteless, classless, and free from suffering, which has inspired anti-caste movements in India. The poster below attempts to recreate this utopian idea.